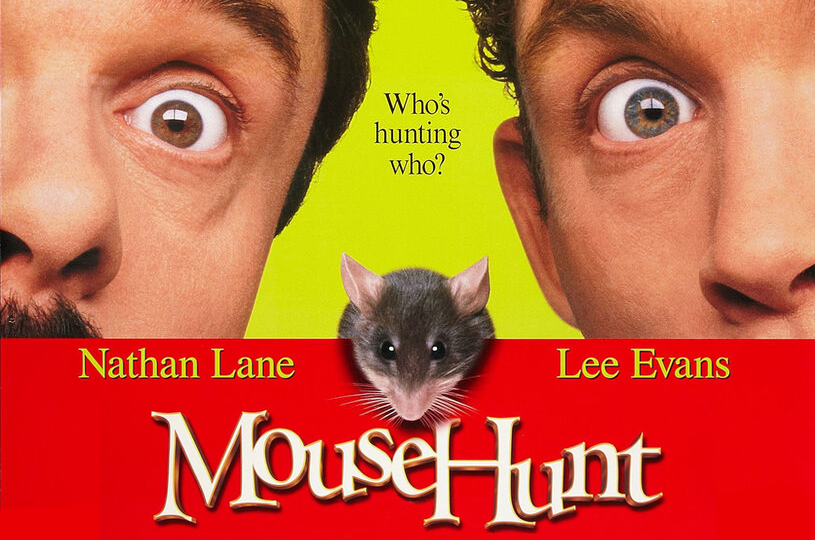

Before Gore Verbinski captivated audiences with the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise and before he won the Academy Award for Rango, his feature directorial debut was the financially successful yet critically divisive comedy Mouse Hunt. With a darkly comic script penned by Adam Rifkin (Small Soldiers, Detroit Rock City), led by the infectiously entertaining duo of Nathan Lane and Lee Evans, and with an unforgettable cartoonish performance from the legendary Christopher Walken, Mouse Hunt is the kind of absurdly unique film that deserves to be regarded as a cult classic.

Originally released by the then-new motion picture production company DreamWorks Pictures, Mouse Hunt was one of three of the studio’s debut feature films—along with the action thriller The Peacemaker and Steven Spielberg’s Amistad. Though I wasn’t fortunate enough to see Mouse Hunt during its initial theatrical release, my first experience came through a rental VHS copy. As an adolescent, I had a deep fondness for slapstick comedy. I’d watch reruns of Tom and Jerry on Cartoon Network, videotapes of The Three Stooges, and episodes of Rocko’s Modern Life on Nickelodeon. This style of physical comedy helped shape my sense of humor, and Mouse Hunt appealed directly to those sensibilities.

What sets Mouse Hunt apart from other family comedies of its time is Gore Verbinski’s decision to avoid making the film strictly for children. Famed author and scholar C.S. Lewis (The Chronicles of Narnia) once said, “A children’s story that can only be enjoyed by children is not a good children’s story in the slightest,” a sentiment that seems to align with Verbinski’s approach. The film’s atmosphere evokes the dark, dystopian tone often seen in the works of filmmakers Terry Gilliam and the Coen brothers, blending black comedy with physical humor with outstanding results,

Seven years prior, Home Alone was a massive success at the box office, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1990 and one of the best-selling home video releases of its time. Its influence on Hollywood family comedies was undeniable—everyone wanted a piece of the McCallister pie, from Blank Check, Dunston Checks In, and even John Hughes’ own Baby’s Day Out. The model of a family comedy with cartoonish hijinks was seen as an easy buck. While Home Alone had set the bar, Mouse Hunt offers something darker and more nuanced, with a unique comedic style that takes it beyond the typical formula.

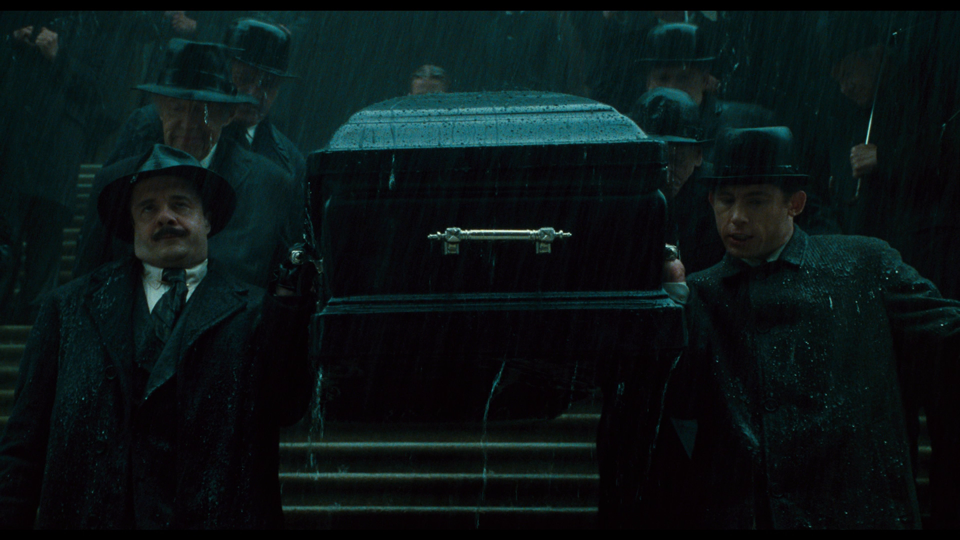

At first glance, it’s fair to assume that Mouse Hunt is just another Home Alone-inspired cash grab, but from its opening scene, it becomes clear that we’re in for something truly unique. Starting with a very cheerful setting: a funeral. The Smuntz brothers bicker over a trivial thing—Lars is wearing what Ernie considers a charcoal suit instead of the appropriate black. Mid-argument, a casket handle snaps, sending their father’s body tumbling down the church steps and straight into an open manhole. This over-the-top gag, set against the morbid backdrop, perfectly establishes the film’s distinct brand of dark comedy—one which will entertain adults while introducing younger viewers to a more twisted sense of humor.

While many notable names—such as Jim Carrey and Nicolas Cage—were considered for roles in the film, the casting of Nathan Lane (The Lion King, The Birdcage) and Lee Evans (The Fifth Element, There’s Something About Mary) proved to greatly benefit the film. Although bigger stars may have drawn a larger audience, Lane and Evans deliver a memorable on-screen dynamic that may have been lost had more recognizable faces been attached to these characters. Lane, a beloved stage and screen veteran with his larger-than-life personality and irresistible charm, portrays Ernie Smuntz with the appropriate amount of cynical wit to elevate the macabre humor. Paired with the domestically unknown Evans as his hapless, optimistic brother Lars, who delivers a brilliant rubber-limbed physicality, the film provides him with the ideal platform to showcase his exceptional physical comedy to new audiences.

Complementing its lead duo, Mouse Hunt features an impressive supporting cast, including legendary character actor Michael Jeter (The Fisher King, The Green Mile) in the small but memorable role of architect historian Quincy Thrope; William Hickey (Prizzi’s Honor, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation) in one of his final film roles as the string magnate and brothers’ father, Rudolph Smuntz; and, most notably, Christopher Walken (The Deer Hunter, Pulp Fiction) as the scene-stealing, eccentric exterminator, Ceaser. While each actor brings a zany, idiosyncratic appeal to their performances, Walken’s earnest portrayal of the unhinged pest-control expert is easily the standout. Much like his unforgettable appearance in Annie Hall, his reserved tone while delivering such insane dialogue creates an excellent contrast, amplifying the comedy and making every line hit with big laughs.

Of course, the true star of the film is the mouse itself. Brought to life through a combination of trained animals, computer animation, and animatronic puppets created by Stan Winston Studio (Jurassic Park, Terminator 2: Judgement Day). Winston’s team—which included Shane Patrick Mahan (Iron Man, The Shape of Water) and Paul Mejias (The Avengers, Pacific Rim)—applied the same level of masterful craftsmanship as seen in their other works to the rascally field mouse with an impressive, anthropomorphic quality that brings to mind the lifelike puppetry seen in Babe, an apt comparison as the same visual effects house, Rhythm and Hues Studios, worked on both films.

A few critics at the time took issue with the titular mouse’s lack of a defined personality. Roger Ebert referred to him as “simply an ingenious prop,” while Adrian Martin (in a substantially more positive review) noted that he was “imbued with very little character.” While these critiques are understandable, they overlook the purpose the mouse serves in the story. The mouse isn’t meant to be a fully realized character with an arc; rather, he serves as the catalyst that helps the brothers confront their shortcomings and grow.

In a 1998 interview with Film 98 Report, Verbinski stated, “I don’t really see ‘the mouse’ as having an arc. He’s more of a monk. He’s the same mouse at the beginning of the movie as he is at the end of the movie; the brothers have changed pretty radically. But he’s sort of there to teach them a lesson.” Verbinski’s methodology presents the mouse as less of a character and more of a force of nature. His narrative simplicity is a deliberate and essential element of the film’s core themes of personal growth.

The meticulously crafted framing of cinematographer Phedon Papamichael (Walk the Line, A Complete Unknown) utilizes the kind of composition reminiscent of the works of Chuck Jones to enhance a gag. In the scene where Ernie is stuck in the chimney after he’s shot out like a cartoon character, the camera slowly pans to a shot of the frozen lake, complete with a “Danger Thin Ice” sign to further hilarity. The precise pacing of this scene reinforces the playful but chaotic tone of the film, reminding you to accept the absurd logic and simply fall back and laugh.

There are plenty of sight gags throughout, but one of the most memorable is the famous kitchen mousetrap scene. In a desperate attempt to finally catch the mouse, Ernie and Lars set up an excessive number of mousetraps in their kitchen. After foolishly cornering themselves, they are forced to spend the night there, watching in disbelief the next morning as the mouse narrowly avoids every trap. As the mouse makes its way to the top of the fridge, it launches a cherry, triggering a chain reaction that sets off every mousetrap in the room. The brothers scream and flail in panic as the traps snap around them. This moment of pure, chaotic hilarity serves as the film’s comedic centerpiece, and the studio must have thought so as well, given its inclusion in the theatrical trailer and every television advertisement.

Masterful composer Alan Silvestri (Back to the Future, Who Framed Roger Rabbit) orchestrates a magnificent arrangement of whimsical and humorous tunes that complement the film’s absurd, cartoonish antics. The ingenious use of percussion instruments to mimic the scurrying of a mouse, paired with the buffoonish brass that reflects the male leads’ incompetence, amplifies the mischievous energy of its star, perfectly enhancing the madness on screen.

A key element of a film score’s quality is its memorability—whether through an iconic track or a hummable motif that lingers in your mind as the credits roll. Silvestri has crafted a plethora of unforgettable movie themes, from the triumphant fanfare of Back to the Future to the somber nocturne of Forrest Gump; Mouse Hunt is no exception. Its “Mouse Theme” leitmotif, a playful tune that recurs throughout the soundtrack, gives the film a musical identity filled with decadent, childlike whimsy.

One of the notable ways Mouse Hunt pays loving tribute to its vaudevillian ancestors is with its anachronistic setting. Through an eclectic mix of fashion and automobiles spanning the 1940s to the 1990s, production designer Linda DeScenna (Blade Runner, Galaxy Quest) and costume designer Jill M. Ohanneson (Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Firefly) create a magnificent vintage aesthetic evoking a nostalgic lens that honors its cinematic ancestors while remaining accessible to younger audiences.

With all the laudable qualities the film possesses, it’s a shame it hasn’t enjoyed the kind of enduring legacy shared by other iconic comedies of its time—or the bygone era it pays tribute to. From a distance, Mouse Hunt may appear as a critical flop that never quite escaped the shadow of late ‘90s family films. However, there’s much more to appreciate in this movie than meets the eye. It is an outstanding debut for a visionary director, boasting a stellar cast of comedic talent, complemented by a unique script and a majestic musical score. These elements combine to create an unforgettable, laugh-out-loud romp that will entertain children and adults alike.

As the landscape of comedy films has become a sterile sea of uninspired, shot-reverse-shot structures filled with comedians ad-libbing through their scenes, we need more movies like Mouse Hunt to serve as harbingers of classic-style comedies for new audiences. Hundreds of Beavers did this to great success, but I hope more will rediscover Mouse Hunt and recognize it for the avant-garde farce it always was.

You should record yourself reading this and upload it to YouTube as a video essay

I had never knew this existed until now

I haven’t seen this movie yet, however it seems delightful classic that I will consider watching.